Iron is one of the key minerals that our bodies need. This article will give you an overview of the key information that you need to know.

Iron is the carrier of oxygen in the blood, via haemoglobin, to the tissues of the body (Mann & Truswell, 2020). Haemoglobin is a complex giant molecule that at the centre of its four base components holds a single atom of iron. As the iron accepts oxygen it turns to that bright red colour – giving blood its signature colour.

One of my favourite analogies for what iron does goes as follows:

Heme & Non-Heme Iron

There are two types of Iron in the environment – heme and non-heme.

Heme iron is more easily absorbed than non-heme iron. This is because the amino acids in proteins tend to chelate (a type of bonding) the iron and help carry it into the system. Studies have shown that free (unchelted) irons often react with other things in the intestinal tract, forming an insoluble and inaccessible compound or it tends to attach itself to the intestinal lining because of its positive charge. The absorption of chelated ions is three-fold that of free ionic forms. Also, iron has the unique ability to change valances, so it can have either two or three electrical charges through taking up or letting go of an oxygen atom (Ballentine, 2007). This produces ferrous (Fe2+) or ferric (Fe3+) compounds.

How is iron absorbed?

The table below outlines the four stages of absorption (Mann & Truswell, 2011):

| Phase 1 – Luminal Phase | Phase 2 – Mucosal Uptake | Phase 3 – Intracellular Phase | Phase 4 – Release Stage |

| Iron from food is solubilized, largely by acid secretion in the stomach and is presented to the proximal duodenum, where most iron absorption takes place. | This depends on iron binding to the brush border of the apical cells of the duodenal mucosa and the transport of iron into the cells. Non-heme iron – has to be in ferrous form before it can be transported across the cell membrane by a divalent metal transporter (DTM1). | It can come from either source and is stored in the storage protein – ferritin or it is transported directly to the opposite side of the cell and released. | Iron is oxidised to the ferric form by a membrane bound ferroxidase. Hephaestin is released by a specialised iron transporter, ferroportin, into the portal circulation, where it is bound to the transporter protein transferrin. This keeps it non-reactive in circulation. |

After the final stage, 80% of the iron in circulation is transported directly to the bone marrow, where it is incorporated into the haemoglobin.

Due to the different factors affecting absorption there are different recommended daily intakes depending on an individual’s diet:

Also, it is important to note that Iron absorption is hindered by tea and coffee intake. Therefore having tea / coffee and say orange juice (with vitamin C) wouldn’t provide much absorption.

What happens if I have an iron deficiency?

Iron deficiency can cause anaemia; which is the decrease in red blood cells and easily identifiable via a blood test. However, the stores will be depleted before the plasma levels of iron drop; therefore these tests can give a false sense of security (Adamson, 2015).

The most common type of anaemia is Iron-deficiency anaemia; however there are other forms like vitamin-deficiency anaemia (due to low B12 levels) or pregnancy-related anaemia (due to the large amounts of blood used during pregnancy) (American Association Of Hematology, 2020).

Some of the common symptoms are tiredness, fatigue, paleness and tendency of dizziness when standing up (NHS, 2020). Iron deficiency anaemia often occurs in women due to the blood loss during menstruation. It must be noted though that other substances are necessary to build red blood cells too, so it can be a combination of deficiencies that causes the anaemia. For example, copper and magnesium are needed to build blood and adequate levels of protein, calcium, vitamin E, vitamin C & B vitamins are also important.

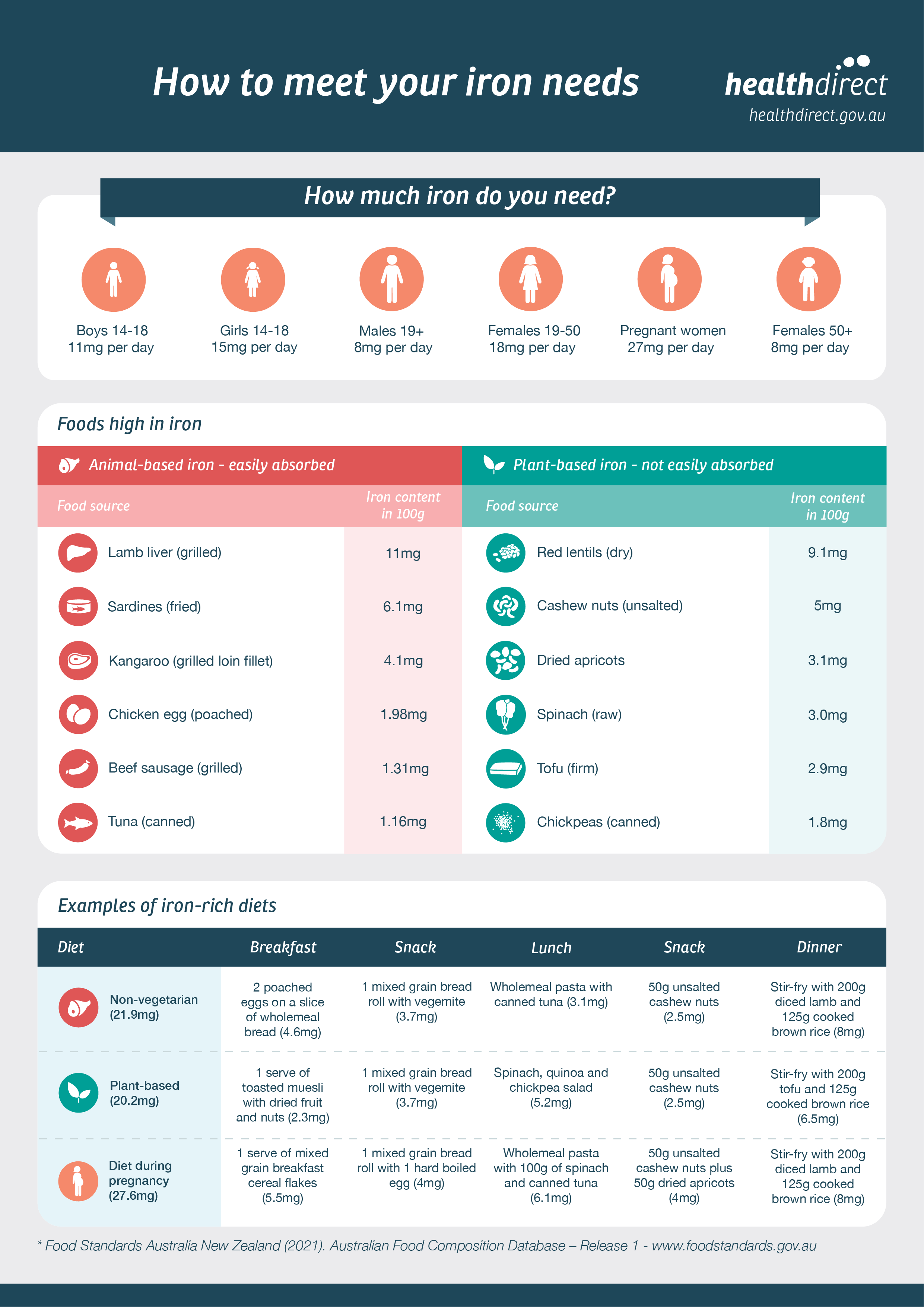

Infographic courtesy of Healthdirect Australia.

Adamson JW. 2015. Iron deficiency and other hypoproliferative anemias. In: Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, eds. Harrison’s online. 18th ed. Access Medicine. www.accessmedicine.com

American Association Of Hematology, 2020. Anemia. [online] Hematology.org. Available at: <https://www.hematology.org/education/patients/anemia> [Accessed 26 May 2020].

Ballentine, R,. 2007. Diet & Nutrition – A Holistic Approach. 2nd ed. Himalayan Institute.

Mann, J. and Truswell, S. ed., 2002. Essentials Of Human Nutrition. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

NHS, 2020. Iron Deficiency Anaemia. [online] nhs.uk. Available at: <https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/iron-deficiency-anaemia/> [Accessed 26 May 2020]

Nuala is a Registered Nutritionist under ANTA in Australia and with the UK’s Association for Nutrition. The clinic is located in at Akasha Integrated Health (Manly) in Sydney’s Northern Beaches in Australia.

menu

latest blogs

© 2023 The Nutritious Way, All Rights Reserved